The advent calendar is a familiar sight in many households each December: a card or box marked with the days until Christmas, sometimes containing a small treat behind each door. Yet this everyday object has a surprisingly rich and layered history. Its origins lie in Christian traditions of preparation for Christmas, and over time it has evolved into a secularised, commercial phenomenon with a wide variety of forms. This essay will explore the theological background of Advent, the earliest practices used to mark the days leading up to Christmas, the advent calendar’s birth in nineteenth-century Germany, its commercialisation in the early twentieth century, and how it spread and transformed in the modern era. The word “Advent” derives from the Latin adventus, meaning “coming” or “arrival”.

In the Western Christian calendar, Advent marks the period of preparation for the celebration of the birth of Christ at Christmas, as well as an expectation of Christ’s second coming.

Although in most use today it refers to the four Sundays preceding Christmas, the precise length of the season can vary annually, depending on the date of the first Sunday of Advent (which falls between 27 November and 3 December). Historically, the observance of Advent stretches back at least to the 4th century, when it was connected with the preparation of new Christians for baptism at Epiphany in January and other spiritual disciplines.

Within this religious context, traditions such as the Advent wreath (with candles lit on successive Sundays) became established.

Thus, the idea of “counting down” or observing the days leading to Christmas has longstanding Christian precedent, rooted in themes of anticipation, reflection, and spiritual preparation.

Long before commercially printed calendars, families and congregations sought ways to mark the passage of days in the Advent season. In 19th-century Germany, Protestant households developed various creative methods: on each day they might draw a chalk line on a door, add a picture to a wall, place a piece of straw in a nativity crib, or light a small candle to denote the day’s passing. For example, according to one account, a “wooden Advent calendar” may have been created around 1851 in Germany.

These practices reflect the same underlying impulse: to provide a visual or tactile way for children and families to experience the gradual approach of Christmas – not simply in terms of days, but in a context of spiritual preparation and hopeful anticipation. The German roots are particularly strong, especially among Lutherans, and from there the tradition began to evolve.

The first commercially produced Advent calendars as we might recognise them today — printed material with numbered days and some form of surprise behind each door — are usually credited to Germany in the early twentieth century. One major figure is Gerhard Lang, a German printer whose childhood memory of his mother sewing small cookies (or pictures) into a box inspired his later commercial venture.

In 1908 Lang released one of the earliest known printed calendars (in partnership with Reichhold) comprising 24 little pictures mounted on cardboard for children to stick each day.

Later in the 1920s he innovated the now-familiar “doors” format — small flaps or windows that could be opened to reveal an image, verse or treat.

According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, German Protestants had begun simple counting-down practices by the nineteenth century, but the leap to printed, commercial calendars occurred in the early 20th century. O

One restriction was in the Second World War, when paper rationing and political regulations (intervened; yet after the war the popularity of printed calendars resurged and spread abroad.

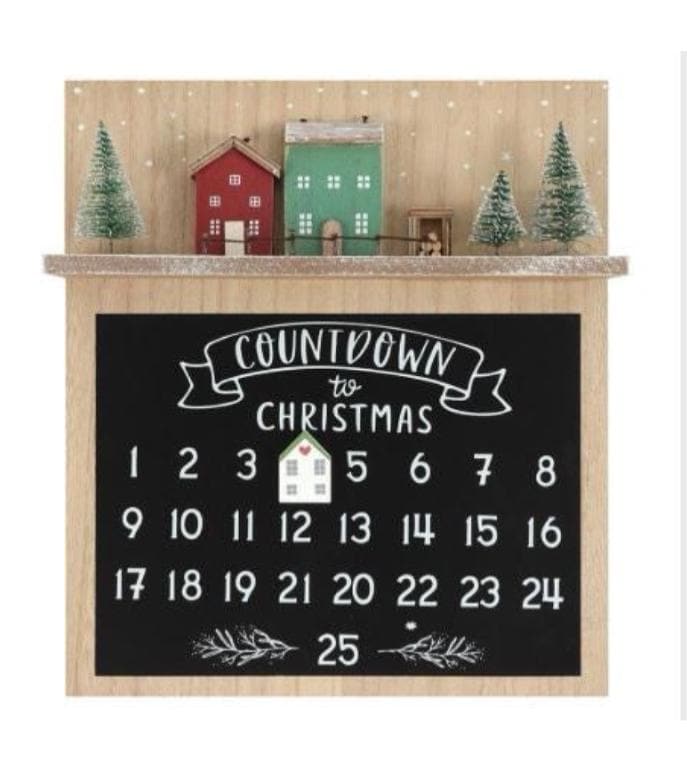

It is interesting to note that although Advent as a liturgical season begins on a Sunday in late November or early December, most commercial Advent calendars begin on 1 December and end on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day — a practical standardisation that allows for uniform manufacturing and retail planning.

By the 1930s, the Advent calendar format had become a fixture in German households and beyond.

After the disruptions of World War II, returning soldiers and cultural exchange helped bring the tradition to the United States and other parts of the world.

In the decades that followed, the nature of the calendar expanded: whereas originally the surprise behind each door might simply have been a picture, later forms incorporated a small gift or chocolate. For example, chocolate-filled Advent calendars are cited as being introduced in the 1950s in Germany.

Over time the concept widened further: calendars for adults, calendars containing beauty products, gourmet items, liquor, even electronics, all followed the pattern of “one reveal per day” in the lead-up to Christmas. Thus what began as a religious preparation device gradually morphed into a broader cultural and commercial phenomenon. The sense of daily anticipation remained, but the object became more secular and accessible. As one article puts it: “What is an Advent calendar? … Roots in German Protestants who created clever ways to count down the days until Christmas.”

Today the advent calendar is used by many families as part of seasonal festive fun. Its original meaning — spiritual preparation, reflection, expectation of Christ’s arrival — may not be at the forefront for all users, but the underlying idea of counting down, marking time and building anticipation remains. At the same time, the sheer diversity of forms the calendar now takes makes it more of a cultural device than a strictly religious one. Critics and historians point out that the use of December 1 as the start, rather than the varying liturgical start of Advent, represents a commercial adaptation. As noted on Reddit and elsewhere: because the actual start of Advent moves each year, fixed-date calendars from December 1 simplify manufacturing and consumer access.

Nonetheless, the tradition maintains a link to its roots: one per day, marking the approach of Christmas, with some element of surprise or treat. Furthermore, the calendar has become an object of nostalgia and ritual: many people recall hanging up calendars, opening a door each day, discovering a picture or a small chocolate, perhaps sharing the moment with family. These experiences, though commercialised, carry echoes of the original devotional practices. The shift from chalk lines and candles to printed doors and chocolates reflects changes in society, manufacturing, and consumption — yet the pattern remains recognizable.