Among the carved bones of the ancients, etched into stone and wood, one rune stands as the whisper of the divine: Ansuz, the rune of the Æsir, of Odin’s breath, of inspiration and speech. In the elder Futhark, Ansuz is the fourth rune, shaped like a branch reaching skyward — two arms raised from a central trunk, a sign of communication flowing between earth and heaven. Where Fehu speaks of wealth, Uruz of primal strength, and Thurisaz of the giant’s might, Ansuz opens the mouth of meaning itself. It is the moment when the gods breathed spirit into humankind, when chaos first learned to speak its own name.

In the mythic dawn, before speech and order, Odin and his brothers found two lifeless forms upon the seashore. From driftwood, they shaped Ask and Embla, the first humans. Odin gave them önd — the breath of life. This sacred breath was not merely air, but consciousness, voice, and word: the ability to name the world. That same breath is the essence of Ansuz. It is the divine wind that animates and connects, a current moving unseen between thought and expression. To breathe is to speak; to speak is to shape reality. The Norse understood this truth intimately. Their world was spoken into being not through command but through song. The skald’s voice was not mere craft — it was magic, galdr, song-spells that could bless or bind. Every utterance held weight, every sound had power. Ansuz thus represents more than communication; it is the bridge between inspiration (óðr) and articulation (mál). In Odin’s mouth, words became spells. In humankind’s mouth, they became stories.

Odin himself is the patron of Ansuz. Of all gods, he is the most restless seeker of wisdom — the one who traded an eye for sight beyond sight, and hung upon the World Tree for nine nights to learn the runes. When he perceived the runes in agony and ecstasy, he seized them as revelations. Ansuz was among these secrets, a rune through which he could channel divine utterance. In its very name, one hears echoes of “Áss”, meaning “god,” specifically one of the Æsir. In divination, Ansuz is often read as communication, wisdom, inspiration, and divine guidance — but its depth is older than the words that describe it. When Odin speaks through a mortal, it is Ansuz that stirs their lips. When a poet feels the rush of sudden insight, it is the breath of Ansuz that fills their lungs. It is the rune of the oracle, the prophet, and the poet — the rune that makes language sacred. To understand Ansuz is to understand Odin’s paradoxical nature. He is both deceiver and revealer, both whisperer and teacher. His breath may bless or bewilder; his words may heal or hex. Ansuz carries that same ambivalence — communication that can illuminate or ensnare. A gift of speech is a gift of power, and power is never innocent.

Etymologically, Ansuz is related to the Proto-Germanic root ansuz, meaning “god” or “spirit,” and linked further to the Indo-European ansu- — “breath” or “life-force.” Across mythologies, breath is the soul’s twin: the Hebrew ruach, the Greek pneuma, the Sanskrit prāṇa. The Norse, too, knew this mystery — that spirit moves as wind does: unseen yet irresistible. When the winds howl through Yggdrasil’s branches, one hears Odin’s voice. The breath that carries words is the same that stirs storms. Thus, Ansuz is a rune of air, of the sky, and of the spoken charm. In ritual use, it invokes the unseen currents of understanding, the inspiration that comes not from the self but through it. Just as the wind carries seeds to fertile ground, so does Ansuz carry meaning between minds. It is the rune of the teacher and the listener, the messenger and the dreamer. But it also warns: words can deceive. The same breeze that whispers wisdom can turn into a gale of confusion. The old rune poems remind us of this duality. In the Old Norwegian Rune Poem, Ansuz is described as the “oldest of the Æsir,” the “chief god,” and a “source of speech.” Yet that same speech can bring sorrow — as when Odin’s words inflamed heroes to war, or when Loki’s tongue sowed discord among gods.

In the myth of the Mead of Poetry, we see Ansuz in its purest intoxication. After the war between the Æsir and the Vanir, the gods sealed peace by spitting into a jar, from which they fashioned Kvasir, the wisest being. When dwarves slew him and brewed his blood into a mead, the drink became the source of poetic inspiration. Odin, ever hungry for wisdom, stole the mead and carried it in his belly, exhaling it into the world as poetry. That exhalation is the song of Ansuz. To drink from the mead is to breathe divine speech, to let the god’s wind move through the mortal tongue. The poet, in this light, is a vessel — not the creator but the conduit. In every act of genuine inspiration, there is something not entirely human at work, a current that flows from the realm of the gods. Ansuz names that current. When the rune is drawn in divination, it calls for attention to what is being said — and what is not. It speaks of messages, teachers, omens, and intuition. But beyond fortune-telling, it reminds us that language itself is sacred, that to name something is to enter into relation with it. Every rune carved, every word uttered, participates in the act of creation.

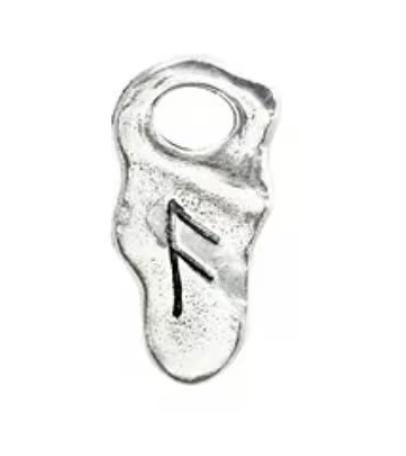

Visually, Ansuz resembles a branching path — a vertical stem with two diagonal arms pointing upward to the right, like the spreading limbs of a tree or the lines of a mouth opening to speak. Its shape recalls both the World Tree and the lungs that breathe life. Its phonetic value, the sound “A,” is the primal vowel — the open mouth, the first sound in most alphabets. It is the sound of awakening, of calling, of awe. To carve Ansuz is to summon that openness — to breathe into the world one’s intention. In magical practice, the rune is inscribed to aid in eloquence, inspiration, and connection to higher wisdom. When chanted, its sound vibrates in the chest like wind in a hollow tree, a reminder that the human body itself is a vessel of the divine voice.

Yet even the god of speech knows silence. Odin, the master of runes, also practices stillness. After he hung on Yggdrasil and seized the runes, he spoke: “Then I fell back from there.” His first act was not to boast but to listen. Ansuz, too, carries this paradox — that silence is the womb of speech. Words gain meaning only when born from stillness, just as breath follows the pause of inhalation. In the rhythm of the world — breath and rest, sound and silence — Ansuz stands at the moment of release, the exhalation that gives shape to spirit. To honor it is to honor both the voice and the void from which the voice arises.